Supporting guidance for Rural Sustainable Drainage Systems – Wetland

This is an old version of the page

Date published: 15 May, 2015

Date superseded: 25 January, 2017

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Benefits

- What needs to be done

- Design guidelines

- Factors affecting performance

- Maintenance

- Further information

- Annex – Identifying run-off types

Introduction

Constructed wetlands are normally shallow ponds and marshy areas covered almost entirely in aquatic vegetation. They are designed to accept run-off that currently discharges direct to a watercourse and to hold it for long enough to allow sediments to settle and for pollutants to be removed through plant uptake and breakdown in the soil.

Designs for wetlands vary widely and can range from single-celled wetlands to systems with multiple stages incorporating other rural sustainable drainage systems features such as swales and ponds.

Benefits

A constructed wetland can improve water quality by treating run-off from a steading or from fields, and can also provide significant biodiversity benefits. They can help to reduce levels of pollutants such as nutrients, bacteria and sediment.

In regards to steadings, wetlands are useful for accepting and treating run-off from clean or lightly contaminated yard areas, preferably as part of a treatment train approach where the wetland accepts run-off from another feature such as a sediment trap and / or a swale.

Wetlands can also be used in-field as part of soil erosion risk management. For example, to capture down slope run-off along field boundaries or alongside farm tracks or roads.

What needs to be done

Drainage from a steading

Where it is proposed that the wetland will take drainage from a steading the first step should be to carry out a drainage assessment. The aim of this is to illustrate which parts of the yard areas will be suitable to be discharged to the wetland. See Annex: Identifying run-off types.

It is important to note that wetlands are not appropriate for accepting more contaminated types of run-off, such as slurry. The Control of Pollution (Silage, Slurry and Agricultural Fuel Oil) (Scotland) Regulations 2003 as amended do, however, allow certain types of run-off that have been contaminated with slurry, such as midden run-off, to be conveyed to a constructed farm wetland.

Such wetlands must be designed in accordance with the Constructed Farm Wetland Design Manual for Scotland and Northern Ireland, 2008. All other types of steading wetlands which have not been designed in accordance with the manual must only accept run-off from clean areas.

Field run-off

For arable situations, the principle aim of the wetland will be to collect overland run-off to allow sediment to drop out. In grassland situations, the purpose may be to capture run-off from a track or road used by livestock or machinery and to discharge it to grassland away from watercourses.

For in-field wetlands, it will be necessary to carry out a simple risk assessment to determine where the wetland should be created to be most effective:

- using a map, such as a copy of the IACS map, highlight all ditches, burns and rivers on the farm or area of land in question

- the next step is to consider where the potential for soil erosion is greatest and where this can pose a risk to the water environment

This assessment should be based on:

- proximity to nearby watercourses – the closer the area is to a watercourse, the greater will be the risk

- slope of the land will be one of the most significant factors – the steeper the downward slope towards the watercourse the greater will be the risk. Slopes of over three degrees (1 in 14) should be considered moderate risk and those above eight degrees (1 in 7) considered high risk. Fields with slopes which tend to converge or fall to a specific low point or corner of the field near to a watercourse will have a particular high risk of causing pollution. Long, uninterrupted slopes are also of greater risk of erosion

- past experience – consider where it has previously been noted that run-off has entered a watercourse or soil erosion has occurred

- soil texture – light soils with a high sand content are at greater risk of erosion

Once the assessment has been completed, identify on the map those areas that are of risk of soil erosion and which may potentially impact on a watercourse. Mark on the map where the wetland system would be best located to intercept the run-off and where it should discharge to.

Design guidelines

Design depends on the type of wetland to be constructed and will be specific to the particular location. As stated above, constructed farm wetlands that are to be used to treat run-off that may be contaminated with slurry must be designed in accordance with the Constructed Farm Wetland Design Manual for Scotland and Northern Ireland, 2008.

For smaller wetlands, which are designed to manage run-off from clean yard areas, there are a number of design criteria that should be observed for optimum pollutant removal, ease of maintenance and safety.

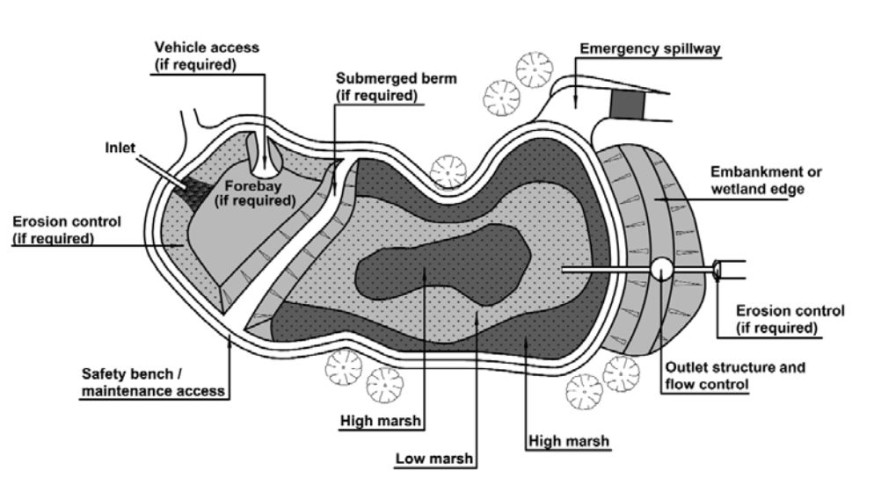

In general:

- length to width ratio should be greater than 3:1

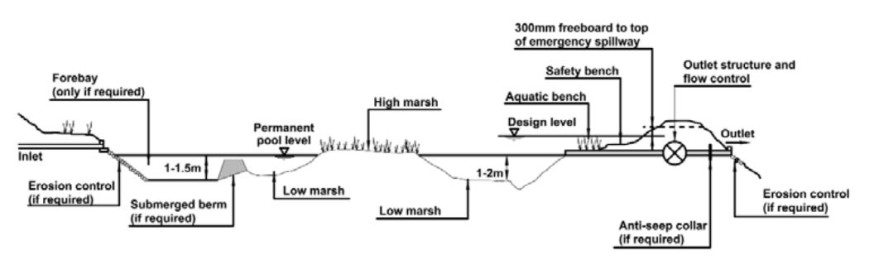

- the depth should be no greater than two metres. Water levels in excess of one metre should not occur over more than 20 per cent of the wetland surface area and the depth of temporary storage above the permanent water level should not exceed 1.5 metres [4]

- shallow vegetated margins should extend across most of pond area if an open water zone is planned [4]

- inclusion of a sediment forebay will extend the life of system and reduce impact on treatment processes and amenity interest

- variable depth profile and shape will enhance biodiversity by providing habitat variety and refuges in event of shock pollution incidents [5]

- an impervious liner is necessary for constructed farm wetlands [3], and for other wetlands with low clay content if the farmer wishes to retain a water level in summer months (fluctuating dry / wet conditions favour breakdown of some pollutants, but may affect release of nutrients from accumulated sediments)

It is important to design for access for excavation of accumulated sediment and plant growth after many years. Long, relatively narrow features, modular systems comprising a series of small units, or shallow marsh features or margins all have merit depending on farm circumstances.

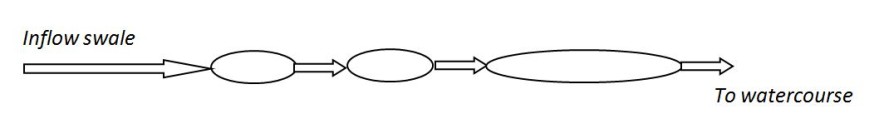

Illustration: three wetland cells in series

Illustration: example design for a shallow constructed wetland (from CIRIA) [4]; designs can be very variable but will incorporate some of these key features

Illustration: cross-section (elevation schematic) of a shallow wetland (from CIRIA) [4]

Using a combination of RSuDS will be more effective than individual measures – the treatment train approach.

Factors affecting performance

- overloading and polluting with accidental spillage of chemicals or slurry. For steading wetlands, such risks can be reduced by taking actions such as effective clean and dirty water separation and good slurry management

- short circuiting and leakage can reduce effectiveness and should be considered at the design stage

- poor flow distribution such that the effective surface area is greatly reduced

- lack of treatment train approach – performance can be enhanced by using grass swales [7] to take run-off prior to the wetland

- wetlands that take run-off with a lot of dissolved soil, such as from arable fields, would benefit from use of silt traps first

- minimise the volume or level of contaminated run-off that the wetland must deal with. On a steading, several localised grass swales (or grass margins serving as a filter strip) may be a more practical option than creating one large feature. Within an arable field, steps such as running tramlines across slopes, relieving compaction etc will help to reduce the risk of soil erosion

Maintenance

- remove silt as required, particularly from the forebay – aim to maintain at least two-thirds capacity

- vegetation management

- checking / clearing any inlets or outlets

Further information

[1] Cooper P (2007). The Constructed Wetland Association UK database of constructed wetland systems. Water Sci & Technol. 2007;56(3):1–6. Also Constructed Wetlands Association

[2] Avery LM (2012). Rural Sustainable Drainage Systems (RSuDS), The Environment Agency, Bristol. ISBN: 978-1-84911-277-2

[3] Carty A, Scholz M, Heal K, Keohane J, Dunne E, Gouriveau F and Mustafa A (2008). Constructed Farm Wetlands (CFW) Design Manual for Scotland and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland Environment Agency and Scottish Environment Protection Agency, 30.10.2008

[4] CIRIA (2007). The SuDS Manual. CIRIA Report C697, CIRIA, London, and book format from www.ciria.org. ISBN: 978-0-86017-697-8

[5] SEPA (2000). Ponds, Pools and Lochans. SEPA, Stirling

[6] Braskerud BC (2001). Sedimentation in Small Constructed Wetlands. Retention of Particles, Phosphorus and Nitrogen in Streams from Arable Watersheds. Doctor Scientiarum Theses 2001:10, Agricultural University of Norway, As, Norway. ISSN: 0802-3220

[7] Northern Ireland Environment Agency (2006). Guidance for Treating Lightly Contaminated Surface Run-off from Pig and Poultry Units. Supplementary Guidance for IPPC Applications. Report prepared by Carole Christian, Environmental Consultant

[8] Mackenzie SM and McIlwraith CI (2013). Constructed farm wetlands – treating agricultural water pollution and enhancing biodiversity. Produced by Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust with Natural England. May 2013

Annex – Identifying run-off types

In general, farm steadings, particularly livestock farms, produce a wide range of run-off ranging from relatively clean roof water to highly contaminated run-off and slurry.

Roof run-off can be considered relatively clean and may already directly discharge to a watercourse. Exceptions may include poultry or pig house roofs with roof vents. Also, any buildings or areas constructed after 1 April, 2007 must be drained by a sustainable drainage system, and roof water can discharge to a closed soakaway or to a watercourse via an infiltration trench or swale.

Yard run-off tends to vary to a greater degree in its polluting load. Therefore, for the purpose of producing the plan for this option, run-off should be classified as:

Slurry

The Control of Pollution (Silage, Slurry and Agricultural Fuel Oil) (Scotland) Regulations 2003 as amended (SSAFO) defines slurry as excreta produced by livestock while in a yard or building and includes a mixture of run-off containing excreta, bedding etc, from yards and buildings used by livestock and middens, weeping wall structures etc.

Run-off from such areas requires to be collected in a slurry storage system. However there is a provision to allow certain types of slurry to be conveyed to a constructed farm wetland that has been designed in accordance with the Constructed Farm Wetland Design Manual. The types of slurry that can be conveyed to such constructed farm wetlands for treatment includes run-off from:

- areas used by livestock occasionally, but excluding areas where livestock regularly move on and off to be milked, housed, fed or gathered

- silos within the period 1 November to 30 April, unless a crop has been added to the silo within this period. This excludes run-off from silos where livestock have access, such as self-feed silos

Lightly contaminated run-off

This could include drainage from yards and areas where livestock do not frequently have access, which are not contaminated with oils and pesticides. It is accepted that such areas will build up a degree of contamination from passing machinery and other activities carried on nearby. In the majority of cases this run-off would be suitable for treatment via a rural sustainable drainage system or alternatively could discharge to local grassed areas.

Dairy washings

This includes washings from the milking parlour and rinsings from the milk storage tank(s), milking machine and ancillary equipment. These types of effluent can be highly polluting and should be collected in a slurry storage facility or a dedicated storage tank.

Pesticide contaminated run-off

Drainage from pesticide handling and loading areas must not be allowed to discharge into a surface water drainage system or a rural sustainable drainage system. There is a capital item available for upgrading pesticide handling facilities.